Response to Intervention (RTI):

Is There a Role for Assistive Technology?

By Dave L. Edyburn

The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 focused national attention on the problems associated with chronic under-achievement by students with disabilities. As federal and state governments have sought to reorganize schools to address the problems of poor academic performance, a model known as Response to Intervention (RTI) has gained favor. RTI models offer a mechanism for designing tiered interventions that become more intensive in response to persistent failure.

As states implement RTI models, it is essential to clarify the relationship of RTI to universal design for learning (UDL) and assistive technology (AT). In particular, it is necessary to understand when poor academic performance will trigger consideration of appropriate technology interventions.

What is RTI?

Response to intervention comes to education from the field of health care. It is easy to understand the notion of intervention and intensive services in the context of illness and disease. Lack of response to an intervention requires new interventions of greater intensity.

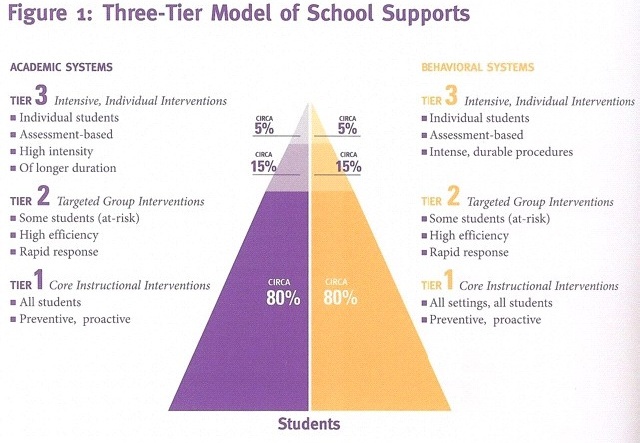

In special education, RTI gained acceptance in the area of positive behavior supports. In this context, Tier 1 involves providing appropriate schoolwide rules and supports to all students in order to prevent behavior problems. However, we know that these techniques will not be effective with all students. Some students will make poor choices, or otherwise fail to succeed, and therefore warrant additional intervention (Tier 2). At this level, small group interventions may assist some studentsí needs and the problem will be solved. However, a small percentage will demonstrate a persistent need for intervention. These students would then be provided with intensive and individualized interventions (Tier 3). The general model is illustrated in Figure 1.

In recent years, some experts have been advancing the argument that a key characteristic of a learning disability is non-responsiveness to instruction. That is, despite being provided the opportunity to learn via high-quality instruction, the student simply does not master the specific instructional objective. Rather than revert back to the historical practice of removing struggling learners from the general classroom, RTI seeks to enhance classroom instruction through the implementation of research-based instructional interventions (Bradley, Danielson, & Doolittle, 2007). These actions are based on the assumption that we can prevent learning problems by providing high-quality instruction to all students. However, by also implementing progress monitoring, we can quickly determine if any student is not benefitting from instruction and work to provide additional, more intensive, interventions (Tier 2). At times there is some confusion about RTI given its application in the context of learning disabilities versus school-wide use.

The U.S. Department of Education does not support any one model of RTI. As a result, a number of models have been developed to describe the relationship between general and specialized interventions. In general, most models involve a tertiary framework, although models involving four or five steps can also be found.

Hoover and Patton (2008) analyzed multiple RTI models and summarized the key features of a three tier model as follows:

Tier 1: High-quality core instruction This refers to high-quality, research-based and systematic instruction in a challenging curriculum in general education.

Expected outcome: Students initially receive quality instruction and achieve expected academic and behavioral goals in the general education setting.

Tier 2: High-quality targeted supplemental instruction This includes targeted and focused interventions to supplement core instruction.

Expected outcome: Students who do not meet general class expectations and who exhibit need for supplemental support receive more targeted instruction. Learners may receive targeted, Tier 2 instruction in the general education classroom or in other settings in the school such as a pullout situation; however, students receive various types of assistance in terms of differentiations, modifications, more specialized equipment, and technology to target instructional needs. Critical within Tier 2 is the documentation of a studentís responses to the interventions used, which serves as important prereferral decision-making data should more formal special education assessment be determined necessary. Students who make insufficient progress in Tier 2 are considered for more intensive specialized interventions and/or formal special education assessment.

Tier 3: High-quality intensive intervention This includes more specialized interventions to meet significant needs, including various disability needs.

Expected outcome: Tier 3 provides students who have more significant needs with intensive, evidence-based interventions within a range of possible educational settings (pp. 196-197).

Understanding Student Performance Data From Three Perspectives

Before examining how technology fits into RTI models, it is necessary to understand that student performance data is viewed differently in the context of assistive technology, universal design for learning, and RTI. This insight has important implications for understanding how and when technology might be viewed as a performance support solution (Edyburn, 2006a, 2006b, 2006c).

In assistive technology, a concern about a studentís performance is subjectively noted and converted into a referral. A referral triggers an assistive technology evaluation. Data may be collected at this point associated with the studentís present level of performance and his or her performance with various assistive technology devices. Ultimately, a device may be purchases based on the recommendations of the evaluation. Typically, followup and follow-along data are not collected on a regular basis so it is difficult or impossible to assess outcome. Assistive technology assessment protocols tend to be informal inventories such as the WATI Assessment and therefore do not integrate with school-wide performance data systems.

In RTI, data is routinely collected and evaluated. Universal screenings are administered to all students in order to gain an early alert of students who may struggle. Progress monitoring tools are used to collect data at regular intervals and the data are plotted. Performance is evaluated in terms of the trend line and a goal line to provide visual evidence about progress. Assessment protocols are commercially available (http://www.studentprogress. org/chart/chart.asp) and are designed to provide data at the school, classroom, and individual student level. As a result, RTI provides an excellent context for measuring student performance. In current models of universal design for learning, student performance data is not collected or evaluated. Likewise, there are no assessment systems to measure and report on student progress in a universally designed learning environment.

Where Does Technology Fit into RTI Models?

Descriptions of RTI typically make little mention of technology. Unfortunately, this communicates a message that technology is not a core tool to be used when designing interventions within each tier. However, letís consider three common forms of technology and analyze their application within RTI.

Universal Design for Learning

The emphasis of universal design for learning on proactively valuing differences makes it an excellent Tier 1 strategy since it will enhance access and performance for all students. Data from universal screenings will help instructional designers build supports and scaffolds into the instructional environment have the potential to prevent academic failure. As a result, it appears that universal design for learning and RTI can be aligned easily and effectively. The shortcomings of universal design for learningís failure to provide student performance data are overlooked in favor of its contributions in the area of class-wide interventions.

Instructional Technology

Clearly there are many attributes (e.g., feedback, error correction, pedagogical agents) of well-designed technology tools and online instructional materials that can support and engage struggling learners. As a result, instructional technology appears to have application in each RTI tier. The primary challenge will be those associated with technology integration (i.e., identifying instructional goals, searching for appropriate tools, evaluating, purchasing, training, and routine use). Instructional technologies may not include robust data collection and student performance monitoring features. However, when they do, these types of products are more likely to be readily adopted by schools implementing RTI.

Assistive Technology

Given the problem that poor performance occurs in all three tiers, when does poor performance trigger consideration of assistive technology? Clearly, some forms of assistive technology (e.g., mobility aids, communication tools, motor and sensory access tools) should be provided outside of the RTI model because it is clear that students will not be able to access, engage, or benefit from instruction in the general curriculum without these tools.

What happens when assistive technology (e.g., text to speech) is provided to all students in Tier 1? This is a challenging question. In many respects, this issue reflects the paradigm shift that is presently underway in the field of special education technology and is being accelerated by the pressure to close the achievement gap. However, by definition, it seems that when an assistive technology is provided to all students, it ceases to be assistive and becomes a universal design support. It seems unlikely that assistive technology, as we now know it, will play a fundamental role in RTI Tier 1.

Failure to perform as expected in Tier 1 can serve as a trigger for assistive technology consideration and meets the definition of more intensive interventions associated with Tier 2. Therefore, consideration of assistive technology in Tier 2 seems to be appropriate. Edyburn (2007) has argued that it is critical to ask the remediation vs. compensation question: How do we determine what percentage of time and effort to devote to remediation and what percentage of time and effort to devote to compensation? That is, how do we decide if the best course of action is remediation (i.e., additional instructional time, different instructional approaches) versus compensation (i.e., recognizing that remediation has failed and that compensatory approaches are needed to produce the desired level of performance)? Because the question about remediation versus compensation is not asked routinely, it is commonly assumed that the only solution is to continue providing instruction and remediation. This oversight must be challenged as RTI is implemented on larger scales.

When students advance to Tier 3 because of their failure to meet performance expectations, serious attention should be given to altering the remediation vs. compensation equation so that the vast majority of the time and effort (70-90%) are devoted to enhancing performance through compensation with assistive technology. Two reasons illustrate why a change in strategy is need: (1) failure to meet performance expectations at this point will take away time from future learning opportunities and, (2) there is overwhelming evidence that traditional instruction and remediation efforts have failed to enable the individual to perform at a satisfactory level.

Concluding Thoughts

A recent online survey conducted by the RTI Action Network found that more than 80% of the 800 respondents rated their knowledge about RTI as ďminimal to none.Ē As a result, much more work needs to be done to build awareness about RTI and to train teachers to utilize these types of methodologies. Advocates of RTI typically have little experience with technology. As a result, technology is not routinely consider to be an essential tool when designing solutions for struggling students. Therefore, technology advocates will need to be much more aggressive to ensure that technology tools continue to be considered as part of the solution set for struggling students. Technology developers will need to become much more committed to creating products that collect data on student performance and generate reports that clearly communicate student progress.

Some forms of assistive technology appear necessary outside of the RTI model. It remains to be seen how the field of assistive technology will address this issue. As readers gain a deeper understanding of the change strategies occurring in their local school district concerning the implementation of RTI, and its impact on the provision of universal design for learning and assistive technology services, leadership is urgently needed to ensure that technology is included in tiered interventions and that appropriate student performance data is collected to provide evidence to inform decision making.

References

Bradley, R., Danielson, L., & Doolittle, J. (2007). Responsiveness to intervention: 1997 to 2007. Teaching Exceptional Children, 39(5), 8-12.

Edyburn, D.L. (2007). Technology enhanced reading performance: Defining a research agenda. Reading Research Quarterly, 42(1), 146-152.

Edyburn, D.L. (2006a). Cognitive prostheses for students with mild disabilities: Is this what assistive technology looks like? Journal of Special Education Technology, 21(4), 62-65.

Edyburn, D.L. (2006b). Re-examining the role of assistive technology in learning. Closing the Gap, 25(5), 10-11, 26.

Edyburn, D.L. (2006c). Failure is not an option: Collecting, reviewing, and acting on evidence for using technology to enhance academic performance. Learning and Leading With Technology, 34(1), 20-23.

Hoover, J.J., & Patton, J.R. (2008). The role of special educator in a multitiered instructional system. Intervention in School and Clinic, 43(4), 195-202.